Reflections on Being a Tourist in the Developing World

We wander down a cramped street in Anomabo, a fishing village along the coast of Ghana. It’s late afternoon and the street is teeming with people, eating and drinking, buying and selling, calling out to one another and to us. We’re causing quite a stir. “Obruni,” the local term for “white person”, echoes up and down the street.

The sun breaks through the clouds, tinging the street with an eerie golden glow. We pass a group of children playing in front of an ancient blue house. Everything here feels ancient, or perhaps timeless; it could be 2014 or 1714. The kids are bathed in light, skipping rope, their shadows dancing on the wall behind them.

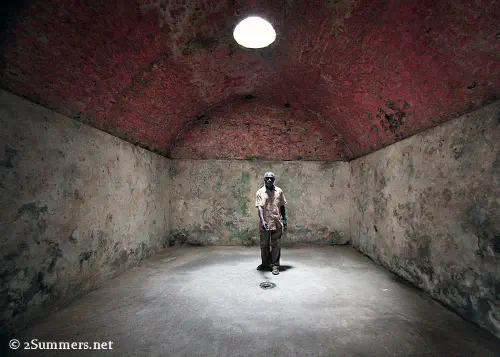

I feel desperate to take a picture – to capture this place that is unlike any place I’ve been before. I turn to Atta, the guide who just gave us a sombre tour of the historic slave-trading fort in Anomabo. “Could you please ask the children’s mothers if it’s okay for me to take a photo?”

Atta addresses the group of women gathered next to the kids. A rapid-fire conversation ensues. “They say it’s okay,” Atta tells me.

I’m not so sure though. One of the women stands up and begins to yank the children by the arms, arranging them in a stiff line in front of the wall. The smallest child cries, and gets a slap.

“No no,” I plead. “No, please don’t.” I look on helplessly, camera in hand, surrounded by shouting and laughing. The kids are lined up now, looking at me expectantly.

It’s not the photo I envisioned. I don’t want to take it. I shouldn’t take it. But I raise the camera to my eye and click.

Ashamed as I am of the circumstances under which it was taken, I think it’s a pretty good photo.

In Akwidaa, another Ghanian fishing village, my friends and I are surrounded by a hoard of children the moment we arrive. “Peechure, peechure, peechure,” they chant, making circles with their fingers and holding their hands to their eyes. “Obruni! Peechure!”

Children in Akwidaa. Note my friends Ken and Michelle in the distance, looking slightly relieved that the children have abandoned them and run toward me. Again, I can’t deny that I like the photo.

If I have a hand free, it is instantly gripped by a child. I eventually start holding my camera with two hands. (Photo: Ken Wichert)

In other places the children – and sometimes the adults – are more direct. “Cash,” demands a small boy, no more than five or six, in the town of Cape Three Points. “Mah friend. Mah friend, cash.”

I don’t take the little boy’s picture and I don’t give him cash. But I can’t blame him for asking.

Everywhere I went in Ghana, I saw things that I wanted to photograph. I’m a photographer and I like taking pictures when I travel. But many times I passed up photos because I felt like an invasive opportunist, or because I was uncertain of the reactions I might receive. Or because I was too tired to deal with the craziness that I knew would ensue the moment I pulled out my camera. Or – perhaps more honestly – because I felt like I owed something after each picture I took.

Sometimes when I did decide to take a photo, especially a photo of children, I felt uncomfortable afterward.

I found myself thinking that to really capture the spirit of one of these fishing villages – which I found so visually stunning and culturally fascinating – I would need to spend several days there, getting to know the people and giving them time to get used to me so I could take pictures of what was actually going on. Maybe with time they would forget that I’m an Obruni and just get on with their lives. Or maybe not. Regardless, my six-day visit to Ghana was too short.

This is one of my favorite pictures from Ghana, mainly because the girl isn’t paying much attention to me.

So I think I took fewer photos on this trip than I have on previous trips. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, though. I experience things differently when my camera is stowed in the camera bag and not in front of my face all the time.

I’m not sure what my point is. This is just something I’ve been thinking about. I’m curious to know what others think.

Cultural anxieties aside, I had an amazing time in Ghana and I’ll be sharing more Ghanaian experiences over the next few weeks.

Comments

Wonderful pictures.

I find myself in the same dilemma, often. Sometimes I don’t even have the courage to ask.

I’m working on changing that. That, and asking my subject to relax, instead of adopting a stiff pose. I try to give back and depending on the circumstance will email a copy of the photo, give a small tip, or if the subject works really nicely, I will take two Polaroids, and give them one.

The other obstacle is getting a model release signed if I feel the shot may be commercially viable. People are extremely averse to signing anything, never mind trying to understand what a model release is. Obviously this is achieved easier in an urban environment, opposed to a rural one.

I like what I’ve seen Marty Cooper do - go back afterwards and give the subjects a print. It’s just not always practical if you or the subject are on the move.

Sometimes we need to remember that we are not merely taking photographs, but making pictures instead.

Thanks for the comment, Timmee. And thanks for the Polaroid – it helps.

I live and work in a township and an informal settlement, and community residents often express (when they finally begin to trust you, as an outsider) their frustration and annoyance at NGO types and missionary slum tourists who like to come and take pictures and use them later in their promotional materials and field reports and such. Where does that money go? Certainly not to the actual people in the photos. I can imagine the dilemma of a photographer, though I am not one myself. It’s similar to the dilemma of a storyteller–whose right is it to tell someone’s story, and is the storyteller allowed to tell it if he/she hasn’t been given permission?

Loved your post ! xoxo

Those beautiful faces are worth so much. Who knows what dreams/destinies reside behind those glittering eyes. Well don!

Thanks – much appreciated.

I got to travel a great deal through my work, almost always without my wife or kids. I often saw things that were interesting and different than anything I had seen before, like plywood shelters, open sewers, kids begging in traffic, or ditches full of broken glass. Pictures of locals are great too but often I just wanted to photograph a thing. But I almost never took pictures of these things because if you are with, say, a local driver or someone from the plant where I was working, taking a picture of the not-so-nice things felt like I would be insulting them and treating their world as a curiosity…. but such things are interesting and I truly did want to show them somehow to my loved ones back home, otherwise how would they ever understand how different things were and what the overall impact of the place was on me. So I’d come back with lots of posed pictures in offices of smiling coworkers I may never meet again. I never resolved this. So I think I can relate.

Thanks so much for the comment, Kyle. I really relate to what you’re saying too. I know how it feels to come back from a place so different from home and not know how to explain it to your loved ones who didn’t go with you. It’s a frustrating and lonely feeling.

Makes me want to go!!

Thanks, that must mean that you liked the post.

No one is more appreciative of the candid moment in photography than I am; but that line-em-up is a classic. I just love it.

Great photo!

Thanks!

I live in a small desert town in the US full of Anglo and Latino families (In some neighborhoods I’m an Obruni in my own town!). My photos are just for my own practice, but often people are suspicious, so I try to talk to them and tell them that they have such beautiful smiles (which they do!). Sometimes this helps. Often I end up with one of those “line up at the wall” shots. But sometimes I can tell they are still very uncomfortable, so I end up not taking pictures no matter how badly I want to. It might be easier if I had credentials from a magazine, something they can understand, but I don’t know. Often they ask, and when I tell them the pictures are just my hobby, sometimes that actually makes it worse! I think today you have to deal with the fact that a lot of “snapshots” end up on Facebook or Twitter for the whole world to see, so sometimes their fear or suspicion is not a matter of money or my being a stranger. It’s “am I putting this child in danger?” – from a pedophile, an angry ex, etc. I got into photography because I love capturing people in everyday life, but it’s become so difficult that I often just decide to put the camera away. In the America I grew up in, people were shy or embarrassed, but generally pleased to have their picture taken. Now I feel like a papparazzo.

That’s a shame. But I totally hear what you’re saying. I think it’s probably more difficult in America than in Africa. But getting harder here too. Anyway great comment - thanks.

I love your thoughts on this, Heather. Something that has always troubled me too. Like you said, it’s an ancient philosophical question almost, as long as journalism has been around. Remember the scene in the Bang-Bang Club where he takes the picture of the starving child and wins a Pulitzer Prize? As a journalist you are always torn between wanting to help and wanting to document, and in a way you can’t actually do both at the same time. You can only tell yourself that you are helping by documenting because telling the story might be the start of something good happening in other ways.

Thanks Sine. The question if how to “help” is a difficult one too. I prefer to think of it from a perspective of compensating people for services provided. Giving a few cents to a child who asks for it is not helping anything, in my opinion, but I did try to purchase some kind of service – buying food or water, hiring a guide, etc. – in every place I went. This is the best way to help I think. I also did sometimes pay adults for the privilege of photographing the work they do, like the coffin-maker and the guy along the road selling rat meat (more on that in a future post). But it’s so tricky.

It’s so sad the kind of life they have to live in. At least it looks like they are having fun.

Wow. I can really understand how torn you must have felt, but the pictures are phenomenal. I’m falling in love with your blog.

The attitudes about taking photos in Africa and parts of rural Asia are vastly different from that found in the United States. The most “natural” photos seem to be the ones where the photographer was able to spend time with the subjects until they felt comfortable about the equipment and the visitor. Have you felt the same photographing in Johannesburg?

Actually not really. People in Joburg tend to be much more laid back about being photographed. The only exceptions - for obvious reasons - are in certain parts of the city where lots of refugees/undocumented immigrants live.

I’ve worked in eastern and western Africa off and on for several years; a couple dozen trips, a few weeks at a time. There are a lot of pictures I couldn’t take.

In one locale, however, pictures were my pathway into the culture. I’d taken the usual photos (with permission); some were stunning. My partner suggested I print the best and deliver them on the next trip. A couple of them were hard to trace back to the subject; one lovely young mother and child photo took me through several neighborhoods and the city marketplace before I was led to the family on the edge of the community. It was a hit, and to make a long story short, they adopted me. Similarly, I framed and delivered a great photo to a young lady’s mom; we’ve mutually adopted each other’s families and have a great relationship. My daughter helped them buy their house. I’m officially godfather to their newborn.

The ‘rowdy neighborhood’, one of my ‘framed and delivered’ destinations has received around 4000 printed photos over the years. They’re on everybody’s living room walls. When I took my wife, the teens treated her like a VIP and dragged her off to meet literally everybody.

Then there were the five teens who kidnapped me! Ok, not kidnapped, but they coerced me into taking them to a neighboring village restaurant for fish and rice. We’re old friends now and have been together off and on over the years.

These days when I show up at one of the family homes, the teens greet me and run off with my cameras to take pictures of everything; my grandma and her goat, my mom’s kiosk, my friends doing cartwheels. I print and deliver on a subsequent trip. It’s purely recreational, always with permission, produces no dependencies or adverse cultural impact, and opens the door for laughter and conversation and mob trips together to the beach or the mountain or to granddad’s house on the other side of the valley.

We’re now past the ‘white weirdo tourist’ phase; I get introduced as family. My teens are grown and married; we’ve helped with their education and equipment for employment. They’ve got kids of their own, now.

My wife and I are deeply thankful for the chance to be in their world rather than just pass through. The camera opened that door.

What a fantastic story, Brian. Thanks so much for taking the time to share it. I agree that photography has a unique ability to connect people in amazing ways. I’ve started carrying a polaroid camera around with me and I take people’s photos and give them away on the spot. I’ve already had a few really nice experiences as a result.

Anyway, good for you for taking the time to build such an amazing relationship with a community. Sounds like it has really enhanced your life and many other lives.

Hello! I just want to say thank you for the post.

You’re welcome :)